Resnik. Ethical Issues in Scientific Publication.

Publish=to make publicly known. What does that mean and how can it be done?

Objektiivsus

Eelmises peatükis kirjeldatud ja potentsiaalselt veaohtlikud tegevused nagu kallutatud andmekogumine, -töötlus, ja interpreteerimine on vaatluse all ka publitseerimisest rääkides. Sarnased põhimõtted kehtivad kõigile publitseerimisprotessi osalistele – autoritele, toimetajatele ja retsensentidele.

Et abistada retsensente, tuleks kirjutada selgelt. Lisaks peab ta loomulikult sisaldama kogu relevantset infot, mis on vajalik kirjutise mõistmiseks. Vajaliku info hulka kuulub teave materjalidest ja andmetest, nendega toimunust, uurimismetoodikast, rahastajatest, uurimiseks vajalikest lubadest ja publikatsiooni staatusest (nt, et pole samaaegselt mujale esitatud). Autori vastutus ei lõppe trükikojas. Kui ilmneb, et tekstis on vigu, tuleb nendega tagantjärele tegeleda.

Toimetajad ja retsensendid peavad oma töös eriti hoolikad olema, sest nemad vastutavad selles süsteemis kvaliteedikontrolli eest. Nende kohus on töö autorit tema puudustest teavitada. Ideaalis peaks hindamine olema vaba isiklikest huvidest. Eelrentsenseerijad on ju sama ala eksperdid, kel on kindlasti teatav koolkondlik või muul alusel põhinev eelistus mõningate teooriate, autorite, ideede, kirjutamisviisi (mitte-emakeeles kirjutatajad!) osas. Sel kombel võib kuritahtlik retsensent anda tekstile negatiivse hinnangu või selle ilmumist muul moel pidurdada. Toimetajatel on selles suhtes veelgi rohkem võimu.

Täielikult avalik retsenseerimine – kõik teavad kõigi nimesid. Kasulik väga väikeste teaduskogukondade puhul, kus nagunii kõik kõiki teavad. Single blind – autor ei tea, kes retsenseeris, aga retsensent teab autori nime. Double blind – kumbki ei tea, kellega tegu. Topeltpimeda vastu on ka kriitikat, sest asjatundlik inimene saab ju viidete jm järgi aru, kes on autor. See aga tähendab, et kurjade kavatsustega retsensent saab mängida, et ta ei tea, kellele ta negatiivse hinnangu andis.

Kriitika peaks lähtuma sisust ja olema ka esitatud nii, et adressaadiks pole mitte autori isik, vaid sisu. Konfidentsiaalsusprobleem – kõik, kes puutuvad käsikirjaga enne avaldamist kokku, on eelistatud seisus võrreldes nendega, kes saavad teksti lugeda pärast avaldamist. See on oluline risk, sest kui autoritel puudub avaldaja suhtes usaldus, kukub praegune publitseerimise süsteem kokku.

Muud probleemid

Publikatsioonide liigid: eelretsenseeritud originaaltöö (kõige mahukam kategooria), eelretsenseeritud varem avaldatud eksperimendi kordused, ülevaateartiklid. Kuigi kehtiv süsteem soosib originaaluurimusi, on ka teised liigid väga olulised. Keegi ei jõua kogu ilmuvat kirjandust läbi lugeda ja on vaja, et kompetentsed inimesed teeksid ilmuvast ülevaateid.

Kohati on teadlastele oluline publitseerida kiiresti. (Meenub J. Watsoni “Kaksikheeliks”, kus kiirustamise põhjus oli konkurents). Näiteks selleks, et saavutada mingi kriitiline publikatsioonide hulk, mis nö annab kaalu. Kiirustamine aga tähendab üldiselt madalakvaliteedilisi publikatsioone. See võib viia ka “väikseima publitseeritava ühikuni” – jagatakse oma andmed tükkideks ja avaldatakse jupikaupa. Ühik on tähtis!

Eetilised, aga madalakvaliteedilise sisuga publikatsioonid ei tee palju kurja, sest vajuvad peagi unustusse. Esile tõusevad paremad. Samas on väga tiheda sõela kasutamine riskantne, kuna häid ideid võib kaduma minna. Seepärast võiks pigem avaldada kui mitte avaldada. Kuid teisest küljest on liigsel avaldamisel ka miinuseid: ajakirjad konkureerivad omavahel ja tahavad avaldada häid asju, keskmine relevantsus läheb alla, kui mass prahi arvel suureneb. Veebis avaldamine on odav ja see võib tähendada kehvema materjali pealekasvu.

Viitamine, kaasautorid

Viisakas on ära märkida, kelle ideid kasutatakse. Selleks saab kasutada kaasautoriks lisamist, viitamist, äramärkimist (acknowledgements). Kõige hullem eksimus siin valdkonnas on plagiarism. Kohati tehakse vigu, kuna ei mäletata, kust mingi teadmine tuli. Osa plagiaate on tahtmatud. Juhtub ka seda, et sama idee süttib mitmes peas.

Autor on see, kes annab töösse märkimisväärse panuse ja vastutab selle eest. Juhtub, et autoriks pannakse ka inimese teadmata – et saada usaldusväärsust juurde, et “kinkida” autorlus, et märkida ära kellegi tahtmatu panus töösse… Laboratooriumi juhatajad, professorid, õppejõud, juhendajad jne. Osadel töödel on sadu autoreid, neist suurem osa “au-autorid”.

Matthew-efekt: tuntud teadlastele viidatakse rohkem kui nende töö seda väärt on.

Intellektuaalomand

Ülevaade USA IP regulatsioonidest. IP formaalsed tüübid: copyright, patent, trademark, trade secrets. Autori õigused on piiratud kontekstiga. Teiste osapoolte juurdepääs IP-le ei ole võrreldav nö tavalise varaga, sest kõik võivad IP-d kasutada, küsimus on vaid, kuidas. Patent kaitseb autori ainuõigust IP-d kommertsialiseerida. Seegi õigus on ajaliselt piiratud (tihti 20 aastat). Patenditaotluses sisalduva kirjelduse detailsuse aste peab olema piisav, et sama ala ekspert suudaks selle kirjelduse järgi IP subjekti valmistada (Täiesti ebareaalne! Ma pole ühtki oma valdkonna, st muusikatarkvara patenti näinud, mille järgi saaks midagi korrata). Ärisaladuse võib teine ettevõte samuti avastada. Sel juhul esmaavastaja eelis kaob.

Entitlement approach vs desert approach. Olemasolevad IP regulatsioonid järgivad “utilitarian approach” põhimõtet – nad kaitsevad pigem tulemust kui protsessi (panust ja pingutust). Arutlus teemal, mis üldse võib patendi subjektiks olla – kas geenid näiteks võiksid olla? Arvutiprogrammid, valemid, organismid, rohud jne.?

Teadus, meedia ja avalikkus

Teadus ja meedia tegelevad mõlemad info kogumisega, hindavad täpsust ja objektiivsust. Vähemasti uudismeedia kuulub sellesse seltskonda. Teadus soovib samuti meedia kaudu avalikkust teavitada. Näide: uudis mõnest kosmoseavastusest “ei põle”, aga on PR tööriistana toimiv. Probleem: kas pressikal välja öeldud avastus, mille publitseerib ajakirjandus, vastab veel “värskuse” kriteeriumile teadusajakirja mõistes? Teaduse ja meedia suhet on targem reguleerida kui vältida. Selgitamine töötab paremini, kui et lasta inimestel ise “arvata”. Informeeritus on oluline arvamuse kujundaja. Inimest tuleb harida. Paternalism – info moonutamise kolm erinevate astet.

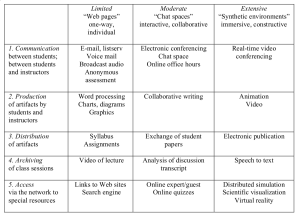

“/…/ it is important that college administrators recognize this and support faculty members in their journeys to integrate instructional technologies, as Loui says “…not merely to duplicate conventional pedagogies, but to promote intellectual engagement.”

“/…/ it is important that college administrators recognize this and support faculty members in their journeys to integrate instructional technologies, as Loui says “…not merely to duplicate conventional pedagogies, but to promote intellectual engagement.”