2012/13 õppeaastal loetud kirjandus

Amador-Campos, J.A., Kirchner-Nebot, T. 1999. Correlations among scores on measures of field dependence-independence cognitive style, cognitive ability, and sustained attention. Perceptual and Motor Skills 88, 236-239.

Armstrong, V. 2011. Technology and the gendering of music education. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Angeli, C., Valanides, N., Kirschner, P. Field dependence–independence and instructional-design effects on learners’ performance with a computer-modeling tool. Computers in Human Behavior 25, 6: 1355–1366.

Baddeley, A. (2010). Working memory. Current biology, 20 (4), R136–R140.

Brändström, S., Wiklund, C., Lundström, E. 2012. Developing distance music education in Arctic Scandinavia: electric guitar teaching and master classes. Music Education Research 14, no. 4: 448-456. doi:10.1080/14613808.2012.703173.

Brünken, J., Seufert, T., Paas, F. 2010. Measuring cognitive load. In Cognitive load theory, ed. Plass, R. Moreno, J. Brünken. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. 1991. Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cognition and Instruction 8: 293-332. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci0804_2.

Chi, T.H. 2009. Active-Constructive-Interactive: A Conceptual Framework for Differentiating Learning Activities. Topics in Cognitive Science 1, 1: 73-105 doi: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2008.01005.x.

Cowan, N., Morey, C. C., Chen, Z. and Bunting, M. F. (2007). What Do Estimates of Working Memory Capacity Tell Us? In N. Osaka, R. Logie, M. D’Esposito (Eds.), The Cognitive Neuroscience of Working Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Daniel, R. 2006. Exploring music instrument teaching and learning environments: video analysis as a means of elucidating process and learning outcomes. Music Education Research 8, 2:191-215.

Dervan, S., McCosker, C., MacDaniel, B., O’Nuallain, C. 2006. Educational multimedia. Current Developments in Technology-Assisted Education (Edited by A. Méndez-Vilas, A. Solano Martín, J.A. Mesa González and J. Mesa González). Badajoz, Spain: Formatex.

Dobbs, S., Furnham, A., McClelland, A. 2011. The effect of background music and noise on the cognitive test performance of introverts and extraverts. Applied Cognitive Psychology 25: 307-313. doi:10.1002/acp.1692.

Ericsson, K. A. (2009). Development of Professional Expertise: Toward Measurement of Expert Performance and Design of Optimal Learning Environments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ericsson, K. A., Prietula, M. J., Cokelyo, E. T. (2007). Making of an Expert. Harvard Business Review July-Aug, 115-121.

Eyuboglu, F., Orhan, F. 2011. Paging and scrolling: Cognitive styles in learning from hypermedia. British Journal of Educational Technology 42, no. 1: 50-65.

Fassbender, E., Richards, D., Bilgin, A., Thompson, W.F., Heiden, W. 2012. VirSchool: the effect of background music and immersive display systems on memory for facts learned in an educational virtual environment. Computers & Education 58: 490-500. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.09.002.

Fogg, B.J. 2009. A Behavior Model for Persuasive Design. Persuasive Technology Lab. Stanford University. http://www.behaviormodel.org/

Furnham, A., Strbac, L. 2002. Music is as distracting as noise: the differential distraction of background music and noise on the cognitive test performance of introverts and extraverts. Ergonomics 45, no. 3: 203-217. doi:10.1080/00140130210121932.

Hamilton, L. 2011. Case studies in educational research. http://www.bera.ac.uk/resources/case-studies-educational-research.

Hayes, J., Allinson, C.W. 1998. Cognitive style and the theory and practice of individual and collective learning in organizations. Human Relations 51, no. 7: 847-871. doi:10.1023/A:1016978926688.

Iznaola, R. (2001). On Practicing: A Manual for Students of Guitar Performance. Pacific: Mel Bay.

Garcia Rodicio, H., Sanchez, E. 2012. Aids to Computer-based Multimedia Learning: A Comparision of Human Tutoring and Computer Support Interactive. Learning Environments 20, 5: 423-439.

Gardner, J.S. 2008. Simultaneous media usage: effects on attention. (Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.)

Gray, R. 2004. Attending to the execution of a complex sensorimotor skill: expertise differences, choking, and slumps. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 10, no. 1: 42–54. doi:10.1037/1076-898X.10.1.42.

Guisande, M.A., Páramo, M.F., Tinajero, M. Fernanda, C., Almeida, L.S. 2007. Field dependence-independence (FDI) cognitive style: An analysis of attentional functioning. Psicothema 19, 4: 572-577.

Kämpfe, J., Sedlmeier, P., Renkewitz, F. 2010. The impact of background music on adult listeners: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Music 39, 424.

Lee, J.J., Hammer, J. 2011. Gamification in education: what, how, why bother? Academic Exchange Quarterly 15, no. 2.

Lin, L., Lee J., Robertson, T. 2011. Reading while watching video: the effect of video content on reading comprehension and media multitasking ability. Educational Computing Research 45, no. 2: 183-201. doi:10.2190/EC.45.2.d.

Liu, T., Lin, Y., Tsai, M., and Paas, F. 2012. “Split-attention and redundancy effects on mobile learning in physical environments.” Computers and Education 58 (1): 172–180. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.007.

Marcus, Gary F. 2012. Musicality: Instinct or acquired skill? Topics in Cognitive Science 4: 498-512

Moreno, R., Mayer, R.E. 2000. A coherence effect in multimedia learning: the case for minimizing irrelevant sounds in the design of multimedia instructional messages. Journal of Educational Psychology 92, no. 1: 117-125. doi:10.1037//0022-0663.92.1.117.

Mayer, R.E., Moreno, R. 1998. A split-attention effect in Multimedia learning: Evidence for dual processing systems in working memory. Journal of Educational Psychology 90: 312-320. Accession no. edselc.2-52.0-0032396526.

Mayer, R.E., Moreno, R. 2010. Techniques that reduce extraneous cognitive load and manage intrinsic cognitive load during multimedia learning. In Cognitive load theory, ed. Plass, R. Moreno, J. Brünken. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mikk, J., Luik, P. 2005. Do girls and boys need different electronic books? Innovations in Education & Teaching International 42, no. 2: 167-180. doi:10.1080/14703290500062565.

Miller, W. 2012. iTeaching and Learning: Collegiate Instruction Incorporating Mobile Tablets. Library Technology Reports 48, no. 8: 54-59. Accession no. 84297445.

Muntean, C. I. 2011. Raising engagement in e-learning through gamification. The 6th International Conference on Virtual Learning ICVL 2011. Accessed May 16, 2013, URL: http://www.icvl.eu/2011/disc/icvl/documente/pdf/met/ICVL_ModelsAndMethodologies_paper42.pdf

Pachman, M., Sweller, J., & Kalyuga, S. (2013). Levels of Knowledge and Deliberate Practice. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0032149.

Papageorgi, I., Haddon, E., Creecha, A., Mortonc, F., de Bezenac, C., Himonides, E., Potter, J., Duffy, C., Whytond, T., Welcha, G. 2010. Institutional culture and learning I: perceptions of the learning environment and musicians’ attitudes to learning. Music Education Research 12, no. 2: 151-178. doi:10.1080/14613801003746550.

Partti, H., Karlsen, S. 2010. Reconceptualising musical learning: new media, identity and community in music education. Music Education Research 12, no. 4: 369-382. doi:10.1080/14613808.2010.519381.

Peng, H., Chou, C., Chang, C.-Y. 2008. From virtual environments to physical environments: Exploring interactivity in ubiquitous systems. Educational Technology & Society 11, no. 2: 54-66. Accession no. WOS:000256100600006.

Perry, G.T., Schnaid, F. 2012. A Case Study on the Design of Learning Interfaces. Computers & Education 59: 722-731.

Rees, F., Downs, D. 1995. Interactive television and distance learning. Music Educators Journal 82, no. 2: 21-25. doi:10.2307/3398864.

Repp, B.H. 2005. Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of the tapping literature. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 12, 6: 969-992.

Sweller, J. 1994. Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and instruction 4: 295-312. Accession no. edselc.2-52.0-43949152992.

Wright, D.J., Holmes, P.S., Di Russo, F., Loporto, M., Smith, D. 2012. Differences in cortical activity related to motor planning between experienced guitarists and non-musicians during guitar playing. Human Movement Science 31, 3: 567–577. doi:10.1016/j.humov.2011.07.001

Yin, R. 2009. Case study research : design and methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Yu, P.-T., Lai, Y.-S., Tsai, H.-S., Chang, Y.-H. 2010. Using a multimodal learning system to support music instruction. Educational Technology & Society 13, 3: 151-162. Accession no. WOS:000282274000014

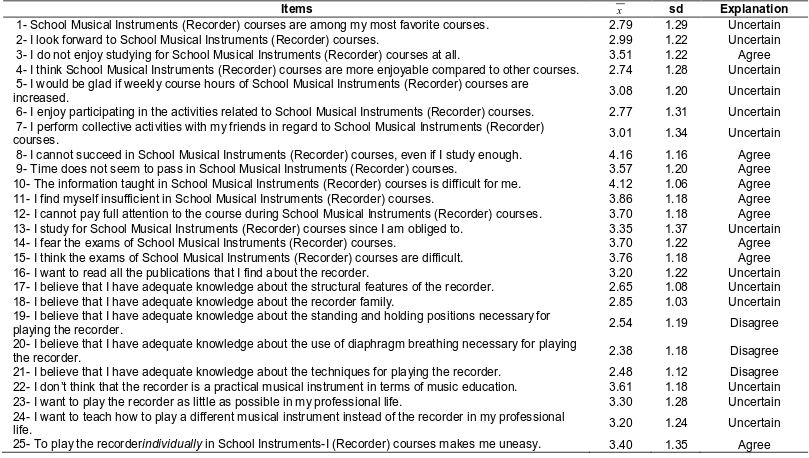

Or as the author puts it: “…prospective music teachers do not love School Musical Instruments (Recorder) courses enough; they do not take interest in these courses; they do not enjoy participating in these courses; and they fear these courses.”

Or as the author puts it: “…prospective music teachers do not love School Musical Instruments (Recorder) courses enough; they do not take interest in these courses; they do not enjoy participating in these courses; and they fear these courses.”