Pike, P. D. (2013). Profiles in Successful Group Piano for Children: A Collective Case Study of Children’s Group-Piano Lessons. Music Education Research, 15(1), 92-106.

From literature overview I get a confirmation that indeed, piano group lessons are very common in the States:

“Teaching adult piano students in groups is quite common throughout North America, particularly at colleges and universities where music majors, who are not pianists, enrol in group piano and theory concurrently. Typically, these students learn as much in 16 weeks as a child enrolled in private piano lessons for two years (Lyke 1996), /…/ Numerous articles have been written on the subject and many benefits of teaching beginning piano to adults using the group instructional approach have been documented (Enoch 1974; Fisher 2010). For children, inclusion of piano classes in public school curricula in the United States began in the early decades of the twentieth century. Historic class methods, materials and teacher instructional materials are the primary source of information about early group-piano endeavours in the United States.”

Further reading: Fisher, C. 2010. Teaching piano in groups. Oxford: Oxford University Press

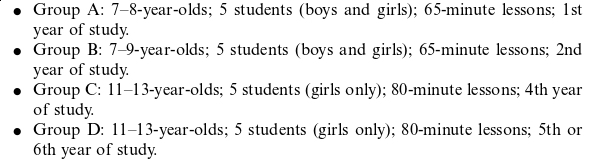

Participants:

Materials for the group A:

- The Music Tree: Time to Begin (Clark, Goss, and Holland 2000a),

- The Music Tree: Writing (Clark, Goss, and Holland 2000b),

- Alfred’s Premier Piano Performance book 1A (Alexander et al. 2005),

- Alfred’s Ensemble book 1 (Kowalchyk and Lancaster 1994) and

- Hal Leonard Ensemble level 1

“Activities included off-bench activities, group dictation at the whiteboard, group rhythm and movement exercises, group discovery at the keyboard, numerous ensemble experiences, performance, sight playing, technique, ear training, improvisation and critical listening activities. There was a balance between playing aloud with the group and playing over headphones, with the instructor being heard through headphones. This allowed students to compare themselves with the ideal performance of the music. Some MIDI accompaniments were used with solo repertoire performance to help students internalise the pulse.”

Everyone on group A were at the same level.

Materials for group B:

- Piano Adventures level 1A or 1B (Faber and Faber 2011),

- Theory Gymnastics: Animato (Zisette, Zundel, and Lloyd 2009),

- Piano Adventures: Christmas book (Faber and Faber 1996) and

- Hal Leonard Ensemble level 1 (Keveren 1996)

Two distinct levels in this group although everyone on their second year.

“When the teacher worked on technique, sight playing and repertoire, she divided the class into two groups (according to skill level). While one group worked together at the acoustic piano, the second group completed written

theory exercises or worked independently on digital keyboards. Ear training, games with manipulatives, and ensemble repertoire were experienced together as a larger group.”

Group C:

- Hal Leonard Lesson, Theory, and Technique books, levels 4 and 5 (Keveren et al. 1996).

- Each girl had a different repertoire book, various individual pieces of sheet music and

- Hal Leonard Ensemble (Keveren 1996)

“When the students played individually, all of the girls gathered around the piano, spotting problems, assessing performance, offering helpful advice and supporting their peers. The students who were not quite as advanced were learning about what they would be doing soon and about upcoming technical requirements. There was a lot of discovery learning occurring during this portion of the lesson.”

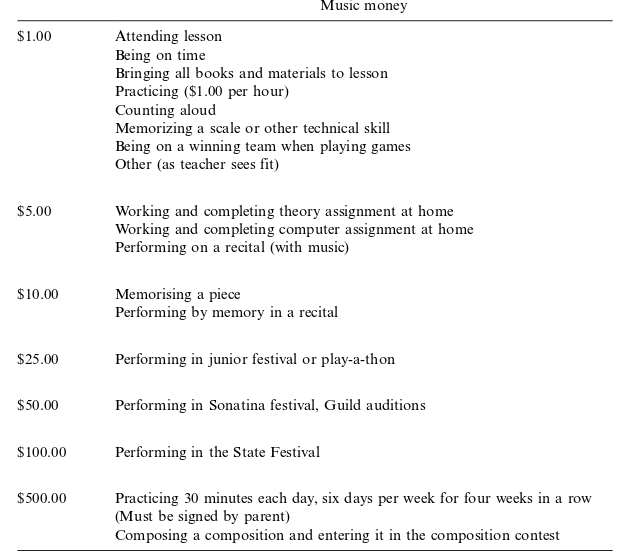

Motivation ideas: ‘Technique Olympics’ at the end of the semester, ‘Music money':

Group D:

- Hal Leonard Lesson, Theory, and Technique books, levels 4 and 5 (Keveren et al. 1996)

- Each student had a different repertoire book

“The in-class activities were more varied and included improvisation, composition, ear training, theory, performance, active listening and even general musicianship through games. /…/ Each of the students performed solo repertoire for 9 to 12 minutes of class time. Students in this class availed of performance with MIDI accompaniments. Each student heard a variety of repertoire throughout the lesson.”