Pike, P. D. (2014). The Differences between Novice and Expert Group-Piano Teaching Strategies: A Case Study and Comparison of Beginning Group Piano Classes. International Journal Of Music Education, 32(2), 213-227.

Abstract:

Pike, P. D. (2014). The Differences between Novice and Expert Group-Piano Teaching Strategies: A Case Study and Comparison of Beginning Group Piano Classes. International Journal Of Music Education, 32(2), 213-227.

Abstract:

Lowe, G. (2012). Lessons for Teachers: What Lower Secondary School Students Tell Us about Learning a Musical Instrument. International Journal Of Music Education, 30(3), 227-243.

Problem: “Retaining students in elective music programs through to the senior years is an international problem. Walker (2003) states that only 5% of the total student cohort in North America enroll in elective music programs in senior school, while Bray (2000) reports only around 2% of students undertake A level music studies in the United Kingdom (UK). In Western Australia three out of four students in the government system cease learning an instrument before their final year of secondary school and, at a federal level, retention has been highlighted as a priority area requiring urgent attention.”

Instrument lessons in West Australia:

Pike, P. D. (2013). Profiles in Successful Group Piano for Children: A Collective Case Study of Children’s Group-Piano Lessons. Music Education Research, 15(1), 92-106.

From literature overview I get a confirmation that indeed, piano group lessons are very common in the States:

“When the students played individually, all of the girls gathered around the piano, spotting problems, assessing performance, offering helpful advice and supporting their peers. The students who were not quite as advanced were learning about what they would be doing soon and about upcoming technical requirements. There was a lot of discovery learning occurring during this portion of the lesson.”

Motivation ideas: ‘Technique Olympics’ at the end of the semester, ‘Music money':

Group D:

Hopkins, M. T. (2013). Teachers’ Practices and Beliefs Regarding Teaching Tuning in Elementary and Middle School Group String Classes. Journal Of Research In Music Education, 61(1), 97-114. doi:10.1177/0022429412473607

Not very relevant to my topic. Still, some knowledge about strings in group: children have problems with tuning in a group setting and teachers often feel they are not instructed to teach that. At the same time only 33% uses electronic tuners. It seems to take 4.5 years to obtain the necessary tuning skills.

Young, M. M. (2013). University-level group piano instruction and professional musicians. Music Education Research, 15(1), 59-73. doi:10.1080/14613808.2012.737773

I mostly care about the literature overview here:

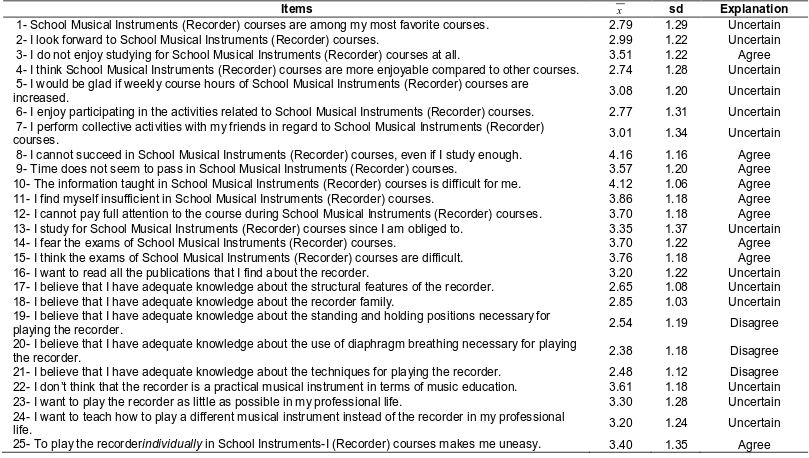

Nobody seems to like studying the recorder in Turkey

Nobody seems to like studying the recorder in Turkey  Or as the author puts it: “…prospective music teachers do not love School Musical Instruments (Recorder) courses enough; they do not take interest in these courses; they do not enjoy participating in these courses; and they fear these courses.”

Or as the author puts it: “…prospective music teachers do not love School Musical Instruments (Recorder) courses enough; they do not take interest in these courses; they do not enjoy participating in these courses; and they fear these courses.”Authors: Ching-I Lu and Margareth Greenwald. Psychology of Music 2015

Similarities between sight reading of musical notation and oral reading. Both are translating print to sound. Mentions Berz (1995) model for musical working memory. Says it’s close to Baddeley’s but just without empirical evidence. That’s bad I guess

For further reading> Berz, W. L. (1995). Working Memory in Music: A Theoretical Model. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, (3). 353.

Salame, P., & Baddeley, A. (1989). Effects of background music on phonological short-term memory. The Quarterly Journal Of Experimental Psychology: Section A, 41(1), 107.

Main takeaway: The diff between musicians and non-musicians was often significant but still small. Music exp may have a small effect on language in case of normally developed people but it has much bigger effect for dyslexics and people with aphasia.

Author: Marcos Vinicius Araujo. Psychology of Music 2015. Seems to be a PhD student’s work.

From literature overview:

(Ericsson etc) Practicing is deliberate when musicians

1) have a well-defined task representing a personal challenge to overcome

2) are concentrating as much as possible during the task

3) have the persistence to repeat sections and correct errors

4) find alternative strategies to try to accomplish difficult elements within the task

Method has problems with sampling validity as many cases were excluded without satisfactory explanations. What characterized the cases that were excluded besides the fact that the questionnaires were incomplete? And a 58 y old with a practicing experience of 56 years? What a talented man…

Results. Time of practicing per day:

< 1 h 22.6%

1-2 hrs 30.7%

2-3 hrs 20.3%

3-4 hrs 16.5%

>4 hrs 9.4%

So let’s see – 53.3% practices less than 2 hrs a day. But that means that it takes more than 20 years to comply with the Ericsson’s 10 000 hrs rule. These people are clearly not on the way to become experts. At least not in music performance. I have tracked the practicing time for years and am pretty much convinced that an 8 hr working day hardly ever contains more than 4 hrs of pure practicing time. Let alone deliberate practicing..

Btw what is the point of giving median values for a 5 point Likert scale – almost straight 4s?

Samuel D. Gosling, Adam A Augustine, Simine Vazire, Nicholas Holtzman, and Sam Gaddis, B.S.

Despite the enormous popularity of Online Social Networking sites (OSNs; e.g., Facebook and Myspace), little research in psychology has been done on them. Two studies examining how personality is reflected in OSNs revealed

several connections between the Big Five personality traits and self-reported Facebook-related behaviors and observable profile information. For example, extraversion predicted not only frequency of Facebook usage (Study 1), but also engagement in the site, with extraverts (vs. introverts) showing traces of higher levels of Facebook activity (Study 2). As in offline contexts, extraverts seek out virtual social engagement, which leaves behind a behavioral residue in the form of friends lists and picture postings. Results suggest that, rather than escaping from or compensating for their offline personality, OSN users appear to extend their offline personalities into the domains of OSNs.

Wu Youyoua, Michal Kosinski, and David Stillwell

Judging others’ personalities is an essential skill in successful social living, as personality is a key driver behind people’s interactions, behaviors, and emotions. Although accurate personality judgments stem from social-cognitive skills, developments in machine learning show that computer models can also make valid judgments. This study compares the accuracy of human and computer-based personality judgments, using a sample of 86,220 volunteers who completed a 100-item personality questionnaire. We show that (i) computer predictions based on a generic digital footprint (Facebook Likes) are more accurate (r = 0.56) than those made by the participants’ Facebook friends using a personality questionnaire (r = 0.49); (ii) computer models show higher interjudge agreement; and (iii) computer personality judgments have higher external validity when predicting life outcomes such as substance use, political attitudes, and physical health; for some outcomes, they even outperform the self-rated personality scores. Computers outpacing humans in personality judgment presents significant opportunities and challenges in the areas of psychological assessment, marketing, and privacy.